CEDAR CITY — How did you spend your summer? Biologists and field technicians with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and their partners were studying a new management tool to help Utah prairie dogs fend off the plague.

The sylvatic plague, caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, can decimate prairie dog populations, with mortality rates of 90% or higher, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Many mammals, including humans, are susceptible to the disease, commonly spread by bacteria-toting fleas.

The bacteria was inadvertently introduced to North America in the early 1900s. Because most native species have “little or no immunity,” they are at risk of death. Prairie dogs are particularly susceptible to plague, which can cause local or regional extinctions, the survey writes.

Utah prairie dogs are federally listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, and are considered a keystone species due to their impact on their ecosystems, Cedar City News previously reported.

Currently, the division dusts prairie dog burrows with a pesticide called Deltamethrin to kill fleas that could transmit the plague, but this is a time-consuming and costly task, Utah Prairie Dog Recovery Biologist Barbara Sugarman told Cedar City News.

FipBits: A new plague management tool

Sugarman was prompted to conduct a study of a new plague management tool after being contacted by David Eads, an ecologist with the Geological Survey’s Fort Collins Science Center in Colorado and Randy Matchett, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The two men had been studying the effectiveness of a new plague FipBits, short for fipronil bites, for black-footed ferrets and prairie dogs. Fipronil is the active ingredient used to prevent fleas in domestic cats and dogs, Sugarman said.

They wanted to know if Utah’s DWR was interested in studying the treatment.

“And I said yes,” Sugarman said. “This is obviously very interesting.”

One of North America’s most endangered mammals, the black-footed ferret, was the catalyst for initial research. According to the Geological Survey, the species was presumed extinct until a colony was found in Wyoming in 1981.

Since then, they’ve seen a comeback due to captive breeding programs and they were reintroduced on the landscape. However, the ferrets remain at risk due to a large reduction in prairie dog populations as they heavily rely on rodents for food and their burrows for shelter.

Ferrets can also contract the plague from flea bites or by eating infected prey animals, the survey writes.

“Obviously, we come from a little bit different perspective,” Sugarman said. “We’re interested in the prairie dogs because they are an at-risk species — there’s no black-footed ferrets here (in Southern Utah) … . That being said, the end goal is the same, so we’ve been working closely with them.”

The fipronil is distributed via baits, or bites, that can be thrown to their destinations from the backs of all-terrain vehicles or walked into colonies from the road. The bites are flavored — often with peanut butter — to entice the prairie dogs to eat them.

Work began in July and was completed for the season in August, taking about four weeks in total. Sugarman said that 75% of the study was funded by a Section 6 grant from Fish and Wildlife, with an additional 25% from Utah’s Endangered Species Mitigation Fund.

One colony the study focused on was one of Bryce Canyon National Park’s largest, which is also recovering from a plague outbreak in the mid-2010s, said Macie Monahan, a wildlife biologist with the American Conservation Experience EPIC Program, who works as a contractor at Bryce Canyon.

“Directly handling the species and getting to see them up close and really getting to, I guess, be hands-on in the park with some of our wildlife has been a really rewarding experience,” she said. “And moving forward with this research, if proven effective, it’s going to save us a lot of time.”

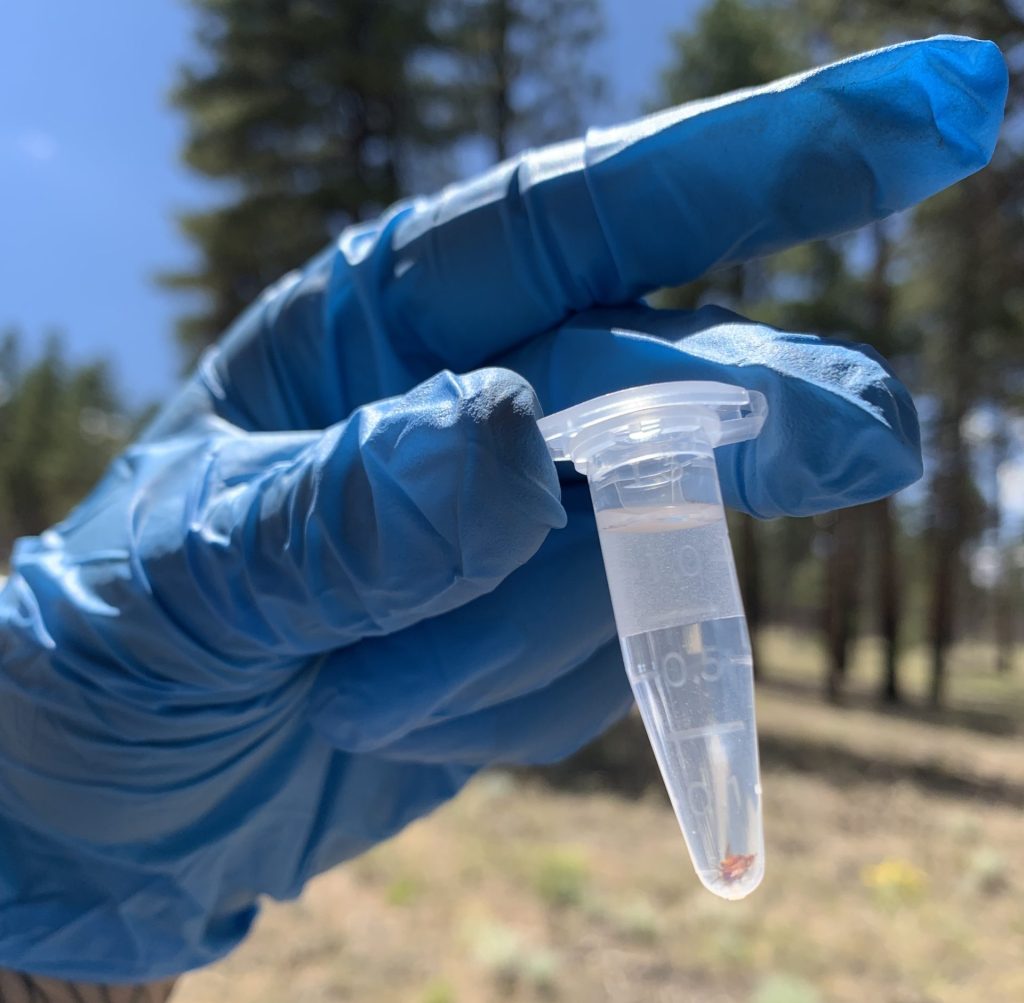

Researchers anesthetized and combed the prairie dogs to gather baseline data about the number of fleas on the animals.

“Unfortunately, we found very few fleas present, likely because the colonies had been dusted with deltamethrin dust last year, and the dust was still effective,” Sugarman wrote in a text message to Cedar City News.

Next year, Sugarman said she hopes to deploy the FipBits, treating half a population or one of two similarly-sized populations. After this, they can compare the number of fleas remaining in both groups of prairie dogs to determine the treatment’s effectiveness.

Judging by previous studies, the treatment could be effective for one to two years, during which time, the division and its partners will continue to monitor the prairie dogs, Sugarman said.

A group effort

The division is working with various partners for the study, including the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Bryce Canyon National Park. This core group of agencies also works together to conduct yearly prairie dog counts and sometimes assists with trapping and translocation.

“I think it’s just a really awesome story of collaboration and working together and working to try to accomplish something that we all want — to be able to help conserve prairie dogs on the landscape as effectively as possible,” Sugarman said. “And … this could be a total game changer for distributing plague management on the landscape and really preventing die-offs potentially.”

Monahan said working with the Utah Prairie Dog recovery team was “the biggest takeaway” from her experience and that she and other participants gained valuable experience from Fish and Wildlife, DWR staff and others.

“Barbara (Sugarman) really cares about this project, and she’s putting a lot of thought and time and effort into making sure it all goes well … . It’s really awesome to see us like working as a unit together — the state and the park,” she said. “And the park supports all this research, and we’re really excited to continue it for next year.”

The pictures and footage of the prairie dog release in the video at the top of this article are courtesy of the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources.

Photo Gallery

A Utah prairie dog eats grass, Cedar City, Utah, Sept. 5, 2023 | Photo by Alysha Lundgren, Cedar City News A Utah prairie dog eats grass, Cedar City, Utah, Sept. 5, 2023 | Photo by Alysha Lundgren, Cedar City News A plague study researcher holds a flea sample, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News A plague study participant holds a Utah prairie dog, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and partners conduct a plague management study, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and partners conduct a plague management study, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and partners conduct a plague management study, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and partners conduct a plague management study, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News Biologist Barbara Sugarman holds a Utah prairie dog, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and partners conduct a plague management study, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and partners conduct a plague management study, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and partners conduct a plague management study, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and partners conduct a plague management study, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News Utah Division of Wildlife Resources and partners conduct a plague management study, date and location unspecified | Photo courtesy of Barbara Sugarman/the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Cedar City News

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2023, all rights reserved.